Katrina Five Ways

An essay originally published in the Summer 2006 issue of The Kenyon Review, reposted here in recognition of the 19th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina.

1. History

Didn’t [s]he ramble . . . [s]he rambled

Rambled all around . . . in and out of town

Didn’t [s]he ramble . . . didn’t [s]he ramble

[S]he rambled till the butcher cut [her] down

—New Orleans Funeral Dirge

On my first trip back, I found New Orleans unspeakably lonely.

The devastation wrought by the levee breaks went on and on, block after block in Lakeview (where I grew up), Mid-City (where my mother lived), the Lower Ninth Ward, and St. Bernard Parish—areas once shimmering with funky life, now lifeless and forlorn. Everywhere dump trucks trolled—FEMA paid by the load. Men with masks directed traffic, sometimes in Hazmat gear. I passed huge dumping areas piling ever higher, flooded cars, blocks and blocks boarded up. I faced one surprise detour after another. Refrigerators taped shut against their stench littered the sidewalks. Many trees and all the grass were dead—drowned. Everywhere I looked for the high-water line— sometimes inches, sometimes feet, sometimes over my head. Gray dust covered everything. It was like being in an old sepia photograph, but with blue sky. In Audubon Park and on St. Charles Avenue there was too much sky: huge holes where live oaks once stood. Birds, too, were gone.

❦❦❦

Reading New Orleans history through the lens of Katrina yields some bitter ironies. New Orleans long thought of itself as “nature’s chosen city . . . superior to any other place on the globe” (Daily Picayune, 14 September 1853). Served by a network interwoven of river, lakes, and bayous, no other city was better situated to benefit from the Mississippi River trade. In the era of steam, New Orleans became the fifth largest metropolis in the nation, the wealthiest city in America per capita, the third largest port, a position it did not cede until the 1920s.

Called by geographers the “impossible but inevitable city,” New Orleans’ expansion was spun by the Progressive Era when the techno logical control of nature was an article of American faith, second only to our faith in commerce. Edison had brought us the light bulb and Bell the telephone; the Wright Brothers had mastered flight. Roebling had linked Manhattan and Brooklyn. Each was an expression of man’s faith in tech nology and proof of the progress it would beget.

Likewise in New Orleans: in 1883 James Eads had triumphantly controlled troublesome sandbars in the Mississippi with the South Pass jetties that scoured a deeper channel and made possible uninterrupted commerce on the Mississippi. And in 1913 Albert Baldwin Wood of the New Orleans Sewage and Water Board built the screw pumps that were so effective in draining New Orleans that the Dutch imitated them to drain the Zuider Zee.

In November 2005, the Times Picayune set an 1880 map of New Orleans alongside a post-Katrina map; backswamp—the wetlands that once lay between the city and lake—and flood were an exact match. The levee breaks had rolled back the calendar 125 years.

After Katrina, pundits wondered aloud how our forefathers could have been so foolish to think that technology could hold back the sea from a city half below sea level. But, of course we built on the drained back swamps. Our imperial view of nature was our hubris—or stupidity if you will—but it was America’s hubris and stupidity writ small. In this, as in so much else, New Orleans is the soul of America.

❦❦❦

When my family founded the Fertel Loan Office in 1895, Rampart Street was on the edge of Back o’ Town where the backswamp had once begun. “Rampart” referred to the levee built along the verge of the old city to keep out flooding from the backswamp.

Built by plantation owners whose forty arpents fronted the river, rural levees were neither as high nor as well made as the city’s better financed levees. Upriver levee breaks, called crevasses, could send water into New Orleans by way of the backswamp. In 1849, water from the Sauvé Plantation crevasse found its way seventeen miles down to the city. Stand ing six feet in the backswamp, its waters reached Rampart Street and three blocks into the French Quarter. Two hundred city blocks were flooded for seven weeks and displaced twelve thousand people from their homes.

Draining the backswamp was as important as constantly raising the river levee. Both imperial gestures would have unintended conse quences that worsened Katrina’s effects.

In 1850 civil engineer Charles Ellet argued (in the federally com missioned Report on the Overflows of the Delta of the Mississippi River) that by stealing the natural floodplain from the Mississippi, the levees were making river stages—or flood levels—annually higher. The Delta and its marshlands went begging for silt. Outlets or spillways were the simple solution and, just as important, would have helped renew the marshlands in the Delta that help protect New Orleans from hurricane winds and storm surge.

But Andrew Humphries, head of the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, believed that levees made currents stronger, scouring out the river bot tom, and thus lowering river levels. This last wasn’t true, but the Corps’ policy remained in force until the catastrophic flood of 1927 when the Mississippi took back its floodplain. New Orleans was saved when the levees were dynamited below the city, creating a spillway like civil engineer Ellet had recommended seventy-five years before. The crevasse lowered the river at the expense of St. Bernard Parish.

The official levees-only policy had another consequence. The levees prevented the annual inundations that renewed the land. Alluvial soil that is not renewed, subsides. The bowl got deeper.

Draining the backswamp compounded the problem. Lowering the water table, always so close to the surface, increased subsidence. The bowl got ever deeper.

According to an e-mail from John William Hall of the Army Corps of Engineers, “a quick and dirty estimate” revealed that Katrina flooded five thousand city blocks. Where in 1849 the water had reached six feet, in 2005 in some places the water reached twenty.

2. Loss

“New Wawyins didn’t die of natural causes. She was moidered.”

—Dr. John

For many years, I proudly gave my “Fertel Funky Tour” to friends visiting New Orleans, emphasizing sites that the tour buses mostly missed. We would lunch at Uglesich’s or Willie Mae’s Scotch House. I would show them the crossroads of Orleans and Broad—an unheralded New Orleans power nexus—where stood Ruth’s Chris, the restaurant founded by my mother in 1965 and, catty-corner, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, the black Mardi Gras krewe of which Louis Armstrong was once king. Across the street lay F&F Candle and Botanical, a voodoo supply shop where my visitors would ogle the gris gris jars and the votive candles to Saint Expedite, for those who seek rapid solutions, and Saint Jude, the patron saint of lost causes.

Rampart Street and its jazz history was another important stop. I would always take my guests by the corner where the Fertel Loan Office once stood and then walk them two blocks up to Perdido and Rampart where a young Louis Armstrong got his first cornet from Jake Fink, a Fertel relative by marriage. At that corner Little Louis was lost and found: arrested for firing a weapon and sent to the Colored Waifs Home where he got his first musical instruction. American and world culture would never be the same.

Now, after Katrina, Perdido Street is lost again. Rampart Street saw nearly three feet of water.

Once, my Parisian guests politely asked, “What ees thees ‘funky’?” I explained that “funky” first of all means smelly—puant—but in New Orleans we have music called “funk,” a kind of soul music, like that played by the Funky Meters. There was once a club called the Funky Butt where Buddy Bolden played. When I say “funk,” think the roots of jazz and its offspring, with a syncopated, heavy back beat, the kind of music, to paraphrase Danny Barker, you gotta dance to unless there’s something wrong with you.

In the first months following Katrina, the original meaning of “funk” could no longer be escaped. People speculated about the source: was it the smell of those still entombed beneath their roofs? the smell of fifty thousand refrigerators now on the street after weeks without electricity? or the smell of sludge the flood waters left behind? Now commercial “Disaster Tours” cover much of the territory that once delighted my guests.

❦❦❦

“Honey, I lost everything,” Willie Mae Seaton told me, sitting out front while the Southern Foodways Alliance of Oxford, Mississippi, gutted and restored her Scotch House Restaurant. In 2005, at age eighty-nine, Willie Mae Seaton received a James Beard Award for more than three decades of heavenly fried chicken and “bread pudding that limns the platonic ideal.” Once, if the black power elite wasn’t doing deals at Ruth’s Chris, they were doing them at Willie Mae’s. Four months after the awards ceremony, five feet of water left behind a pudding of silt. The flagship Ruth’s Chris, four blocks away at Broad and Orleans, is gone too, perhaps for good.

❦❦❦

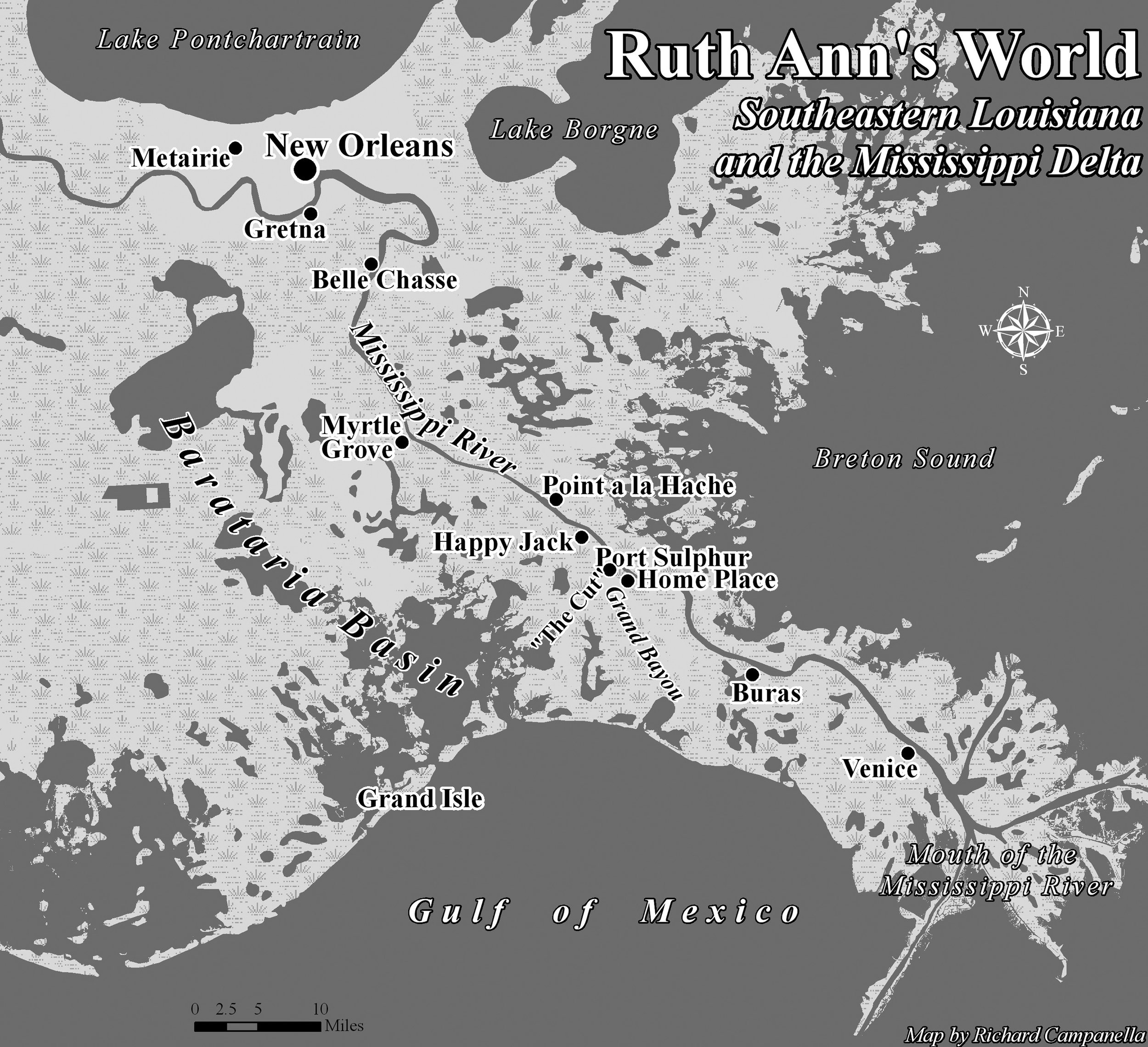

Mom grew up in Happy Jack, fifty miles downriver from New Orleans but a world away. In 1727, Sister Marie Madeleine Hachard, a French Ursuline nun, described the cornucopian land she saw, traveling by pirogue from the mouth of the river up to New Orleans:

There are great wild forests inhabited solely by beasts of all colors, ser pents, adders, scorpions, crocodiles, vipers, toads, and others which did us no harm even though they came quite near us . . . There are oysters and carps of prodigious size and delicious flavor. As for the other fish, there are none in France like them. They are large monster fish that are fairly good. We also eat watermelons and French melons and sweet potatoes which are large roots that are cooked in the coals like chestnuts. . . . Reverend Father de Beaubois has the finest garden in the city. It is full of orange trees which bear as beautiful and as sweet an orange as those of Cape Francis [in Saint-Domingue, later Haiti]. He gave us about three hundred sour ones which we preserved.

A cloistered teaching sect, the Ursuline nuns founded the first school for girls in America, educating white and black, rich and poor, Hispanic and Native American, free and slave (illegally). The original Ursuline Academy at Chartres and Governor Nichols is the oldest structure in the Mississippi River Valley. In the eighteenth century it was saved when a small statue of the Virgin Mary brought to America during the French Reign of Terror and known as “Sweetheart” was placed in a high window as a fire rampaged through the old Quarter. Just in time, a big wind came and turned the fire away. Thus their patron—Our Lady of Prompt Succor, the Virgin Mary in Need for Help in a Hurry—was born.

Beginning in summer, every Catholic mass in Louisiana includes this invocation: “Through the intercession of our Lady of Prompt Succor may we be spared loss of life and property during this hurricane season.” This year it seemed not to work. The nuns and the thirty neighbors they had housed during the storm were evacuated by boat on the Thursday after Katrina, the first time since 1727 that there was no Ursuline presence in Louisiana. The sisters began to despair, fearing that their Lady had turned Her back on them. Then, in prayer, they realized that Katrina had not hit New Orleans directly—surely Her doing. And, as the prioress Sister Carol Marie Brockland declared on National Public Radio, the flood was not providential but a “man-made disaster.”

❦❦❦

Overnight Katrina washed away twenty-five more square miles of the marsh that made Plaquemines, my mother’s home parish, “the wettest place in the world.” Now it was even wetter.

Katrina just plain flattened Plaquemines Parish. The hurricane’s eye passed directly across the toe of Louisiana’s boot before moving on to the Gulf Coast. Where New Orleans experienced Category 3 winds, and the Gulf Coast Category 4, Plaquemines suffered Category 5: sustained winds of 140 miles per hour with gusts up to 190.

But Katrina’s winds were just her love pats. Muck from the lost marshland smothered 60 percent of the nation’s largest oyster beds, two million acres of public and private grounds yielding 250 million pounds of shucked oysters annually. The storm surge swept across the east bank and across the east bank levee, then across the broad Mississippi (two miles wide at that point) and across the west levee. Starting in Happy Jack and all the way to the end of the road in Venice, the back levee, meant to protect from storm surge coming from the west, held the water in. The salt water drowned five hundred of the one thousand acres of Louisiana navels, the best oranges in America, with less acid and higher brix due to our hot days and cool nights. George Steinbrenner receives an annual shipment. The water sloshed around, floating homes off their foundations. The destruction was as complete as the now infamous Lower 9th Ward. Rural rather than urban, it was not as dense. But it went on for over twenty-five miles.

❦❦❦

Two months after Katrina, I went to Happy Jack to see how Sig’s Antique Restaurant, the first restaurant in our family, had fared. Made of old brick scrounged from old plantation foundations and dating from the late 1950s, perhaps it had withstood the winds and waters.

I stopped to photograph one of the floaters that had drifted up to Highway 23. Just as I was driving away, a second glance revealed the wreck of Sig’s Antique Restaurant, its old-brick arches outside and its huge hand-hewn cypress beams inside collapsed.

❦❦❦

It was disconcerting to come to Venice and the end of the road. Everything beyond is river and marshland. I had not seen Venice since fishing trips in the 1960s and so was not prepared to see the world of machinery and vessels created by Halliburton and Bechtel and their kind, a world that had been mostly water, now blue and gray with steel. Here alone in Plaquemines parish, men seemed hard at work that wasn’t just clean up. Somehow, it seemed connected to that other world—Iraq—where, in the midst of devastation and chaos, the same men manage to prosper.

Katrina swept away 250 years of Alsatian, Dalmatian, Isleño, and African American culture in Plaquemines Parish. But Halliburton and Bechtel are forever.

3. Food

Got my red beans cookin’

Yea my red beans is cookin’

When they get done

I’m gon’ give you some

—Professor Longhair

I suddenly think of a restaurant or shop and realize I don’t know its fate. Or, on automatic pilot, I head for a favorite hamburger joint, drive through several miles of devastation, and then find Bud’s Broiler’s door closed, with a water-line at five feet.

One by one, restaurant reopenings are big news locally, each a salve to the bruised collective soul of New Orleans. Cuvée, Restaurant August, Upperline, K-Paul, Bayona, Emeril’s, then the traditional Creole main line restaurants, Antoine’s and Galatoire’s—each helping us imagine that New Orleans might again become livable. Tasting crabmeat maison again at Galatoire’s made everything momentarily whole: a mound of jumbo lump crabmeat in mayonnaise, lemon, green onions, and I’m not sure what, is sweet beyond sweet and rich beyond rich.

But not just haute cuisine; also basse: when Faubourg St. John’s Parkway Bakery held a gala reopening in late December, one thousand people showed up, looking, according to local food critic Brett Anderson, “like the wedding party of a Mafia prince.” Most came for the famous roast beef poor boy, which serves New Orleans as a kind of terrestrial ambrosia. Best of all, the first taste of a Louisiana navel orange, picked that morning on Johnny Becnel’s family farm, now in its eighth generation, high and dry in Jesuit Bend in upper Plaquemines.

In early December, I attended the gala reopening of Ruth’s Chris in Metairie, our suburban store since the early 1970s. Joe Bruno, an old friend from Mid-City who had owned a string of Tastee Donut shops, expressed his relief: “Randy, I’m so glad they opened. I was SOOOO hungry.”

Like many in the New Orleans diaspora, I longed for the proper ingredients to recreate our food. Five weeks after the storm, I returned to New York from New Orleans with my suitcase filled with Camellia Brand red beans, green baby lima beans, crawfish tails, ham seasonings, and smoked sausage (or, as we say, “smoke sausage”).

4. Race

At a Irish wake in the Irish Channel,

Paddy McGinney was laid out

In his best Irish flannel.

—Dr. John

There is no apology for the racism endemic to New Orleans (and America) that Katrina revealed through images at the Superdome and the Convention Center. Nonetheless, as usual, the media skewed the truth to sell soap. We heard about the lower 9th Ward, but low ground in New Orleans is not exclusively black.

High ground in New Orleans has always fetched a premium. But there are telling exceptions like Dr. John’s Irish Channel, a buffer between the toniest addresses of the Garden District, and the unpleasantness of the wharves. In the early 1990s, I lived there, halfway up the crescent between downtown and uptown. The neighborhood often smelled of diesel, no doubt an improvement on the stench of former times when the port was busier and before containers and refrigeration. New Orleans was the last major American city to install a sewer system; until 1909 human waste was dumped by the tugboat Flora (goddess of flowers) midstream, directly facing the down town area. For Mark Twain New Orleans was “the upholstered sewer.”

Nearby, across Jackson Avenue, lay the notorious St. Thomas proj ect, built in the late 1940s as the city’s first low-income housing project, a cure for tenement slums set up against the river for the same fragrant reasons. “Da Channel”—famous for the chewy accent which stems from the same Irish immigration that gave us Brooklynese—got its name in the day when river pilots set their course by the lights of the district’s Irish bars. The locals, first Irish and German, then African American, worked the wharves and served the Garden District homes. St. Thomas now has been replaced—very controversially—by a mixed income development and a WalMart that, after Katrina, was ransacked every fifteen minutes on the cable news networks.

The Irish Channel and the site of the former St. Thomas projects stayed dry. Middle- and upper-class mostly white homes were flooded in much of Uptown, Old Metairie, Lake Vista, East and West Lakeshore, and Gentilly, as well as all of Lakeview.

❦❦❦

New Orleans’ own responsibility for the calamity runs deep. But the prejudice that has undermined New Orleans civic society goes beyond race. New Orleans was shaped for more than a century by the aristocratic, undemocratic traditions of colonial France and Spain. When the Americans moved into their manses in the Garden District they adapted to a society stratified by parentage rather than ability, a society of exclusion, not inclusion.

When largely Creole blacks, many descended from gens de couleur libre, took power in the late 1970s, they had been operating within that paradigm since the eighteenth century. Mayor Ray Nagin is their heir. New Orleans is a city where Creole clubs like the Autocrat once gave a “paper bag test” at the door (anyone darker than a paper bag couldn’t get in). It is a city where one downtown neighborhood, Treme (Tra-MAY), across Rampart Street from the French Quarter, was known as the “Can’t Tell Ward” because so many light-skinned blacks lived there. The fault of those in the Superdome and the Convention Center was in part that they had failed the paper bag test. Ray Nagin’s ideal Chocolate City would be milk chocolate.

That New Orleans is the most European of American cities is one of our often remarked virtues. It is also one of our gravest vices. The pie seem smaller in New Orleans? Some people seem not to get a share? That vice is an important reason why.

Five years before my mother mortgaged our home and bought Chris Steak House, she began work as a lab technician at Tulane Medical School. A divorced mom with two children, she placed an ad in the paper for a housekeeper. A young African-American woman called to set up an interview but got lost on the bus system and turned up hours late. Mom, tired of waiting, had gone fishing.

When I answered the knock at the door, I learned that Earner Syl vain had “come for the job.” “OK,” I said. It was 1960. I was ten. On the strength of that interview, Earner (pronounced “Earna”) landed a job that lasted till my mother’s death in 2002.

Like my mother, Earner came from the country—Edgard, Louisiana, in St. John the Baptist Parish, about the same distance upriver as Happy Jack is down. Louis Armstrong’s mother MayAnn came from the next town, Boutte.

Earner, who grew up on the banks of the Mississippi, fears water. She will not drive herself over any large bridge. For most of her life this confined her to the Ile de la Nouvelle Orleans surrounded by swamps to the east and west, lake to the north, and river embracing the Crescent City on three sides. Unlike many of her neighbors she had traveled outside New Orleans, sometimes following Miz Ruth to restaurant openings around the country.

❦❦❦

Earner rode out the storm in her home, itself suddenly an island, on Arts and Dorgenois. A neighbor rescued her by boat and took her to the Superdome. Her daughter Connie rode out the storm nearby on Pauger Street, after failing to persuade her mother to leave her house. Connie had worked at Ruth’s Chris for thirty-two years, first as a busser and later as a much-loved waitress. She had many “call parties,” regulars who asked for her by name.

Connie couldn’t say much about the storm because she was so frightened that she hid. The wind was “howling like the evil one.” When the levees broke, the closest three miles from her home, she walked toward the Superdome with water up to her chin. She stands four feet, eleven inches. A boat picked her up and dropped her at the Airline Highway overpass. After waiting from 2:00 to 6:00 A.M., Connie finally walked to the Superdome where, she said, bodies floated in the three feet of water surrounding it.

There Connie found her mother. They spent five or six days in the Dome, at the forty-yard line down by the field. “It was nothing nice,” she said, the story pouring out of her. She saw a man jump from the upper deck to his death. She spoke of the smell and of rumored rapes in dark bathrooms. “People were dropping around you like flies.” Refusing Meals-Ready-to-Eat, she survived on potato chips and water. Finally, in frustration, they walked to the Convention Center where buses were accepting children and the elderly. Connie pleaded that her mother had Alzheimer’s and her sister Sheril had had a small stroke.

Earner Sylvain with Willie Mae Seton of Willie Mae’s Fried Chicken

On the way to the Astrodome, Connie couldn’t take any more of her mother’s “Alzheimer tantrums.” Leaving Earner with Sheril, she got off the bus in the middle of the night in Franklin, near Lafayette in the heart of Cajun country, and started walking. She is still in Franklin, longing to return to New Orleans and Ruth’s Chris where there is a job waiting but no place to live. Connie doesn’t drive.

Earner and Sheril ended up in Fort Worth in a Best Western hotel room paid for by FEMA. My brother Jerry tracked her down and drove her to Hot Springs. Earner can’t remember anyone but Connie and her grand son Pie. She calls Connie to come get her in a cab and take her home. When Connie reminds her where they are, three hundred miles apart, and with no home in New Orleans, Earner slams the phone down.

As I write, my brother Jerry is in New Orleans, restoring Earner’s house with a crew he brought from Hot Springs. No one knows when electricity and water will be restored to her area.

5. Animals

I went on down to the Audubon Zoo

And they all axed for you.

The monkeys axed, the tigers axed,

And the elephants axed me too.

—The Funky Meters

If my mother is famous for her success as a restaurateur, my father is infamous as an unsuccessful politician. In 1969 Rodney Fertel ran for mayor of New Orleans on the platform that the zoo needed a gorilla. Campaigning in safari outfit and pith helmet, his slogan was: “Why vote for those monkeys when you can vote for Fertel and get a gorilla?” He got 308 votes and then went to Singapore, bringing back two baby lowland gorillas; he called them Red Beans and Rice. In his gift to the Audubon Zoo, he announced he was the only candidate in history who had kept all his campaign promises, even though he’d lost.

About eighteen months after Dad’s death in 2003, I received a phone call from Dan Maloney, general curator of the Audubon Zoo, who called to break the sad news: Scotty the Gorilla (a.k.a. Red Beans) had died.

Dan made a point of saying—as if this were a condolence call for a family member—that Scotty seemed to have died in his sleep. They found him in his favorite sleeping spot, a plastic tub. Best of all, Scotty went out as any red-blooded gorilla could wish: he had spent the morning servicing the she-gorillas. His life was what the Times Picayune called “a triumph of preservation.”

❦❦❦

Animals too were part of the Katrina story. Many New Orleanians refused to evacuate after the water rose because their pets, left behind, would perish. Meanwhile extraordinary efforts were made to rescue ani mals. The Louisiana SPCA and the Humane Society of the United States went house to house. The New Yorker reported that for a while the animal rescue workers outnumbered FEMA representatives.

Filmmaker and oral historian Kevin McCaffery, having twice been turned back by National Guard at the Orleans parish line, launched his boat at the Bonnabel boat slip, landed on the Lake Pontchartrain seawall, walked three blocks, and rescued his traumatized but well-supplied and well-fed cat.

❦❦❦

The Audubon Zoo was in some ways a microcosm of the city. Dan Maloney and his skeleton crew hunkered down in the Reptile House to wait out the storm. The zoo lost only four animals. A raccoon drowned, a Bali mynah bird disappeared, and two young otters died, apparently of stress. This number represents less than half a percent of the fifteen hundred animals in the zoo, almost exactly the percentage of New Orleanians lost.

In Katrina’s wake, the zoo mirrored the city in losing 70 percent of its workers. With city funds diminished and ticket sales nearly nil, only 225 of the eight hundred employees could be retained. A former host on the Animal Planet channel, Dan now works the front gate on the weekends, the only days the zoo opens for visitors.

But the most significant loss was the people—locals and tourists—that had made the Audubon Zoo, like the city itself, one of the most vibrant destinations in the world. Dan wrote me: “This was never more evident than in the quiet, lonely months just after the storm. Many of us lived at the zoo throughout the ordeal, and the abnormal stillness began to take a toll on the people and the animals. It became exceedingly clear just how important guests are to defining the true essence of a zoo. Without our visitors enjoying and learning about wildlife in a beautiful and secure setting, we are only a pretty place holding and breeding endangered species.”

Which sounds a lot like the new New Orleans.